Whether they are working with patients in clinical trials or with chromosomes in cell cultures, scientists and physicians in the Boston area and beyond are testing a wide variety of new ways help people with Down syndrome. At the New England Down Syndrome Symposium, presented by the Alana Down Syndrome Center on Nov. 10, a virtual audience of hundreds of people learned about the research progress of a dozen research teams. The Alana Center at MIT partnered with the Massachusetts Down Syndrome Congress and the LuMind IDSC Foundation to organize the daylong program of online talks.

“I am hopeful that the research being done today will improve medical care and the quality of life of people with Down syndrome,” said Kate Bartlett, a member of the Self-Advocate Advisory Council of the MDSC. “Your work is important for me and my peers. Together we can make a better world for all people to lead active, healthy, fulfilling lives.”

Clinical studies

One of the specific health concerns Bartlett, who is 35, called out in her remarks is that the age of onset for Alzheimer’s disease among people with Down syndrome can be as early as 40. Finding ways to address the community’s elevated risk of Alzheimer’s was one of the four main themes of the symposium, along with new potential therapies for sleep apnea, and fundamental research on developmental biology and on chromosome number and dosage.

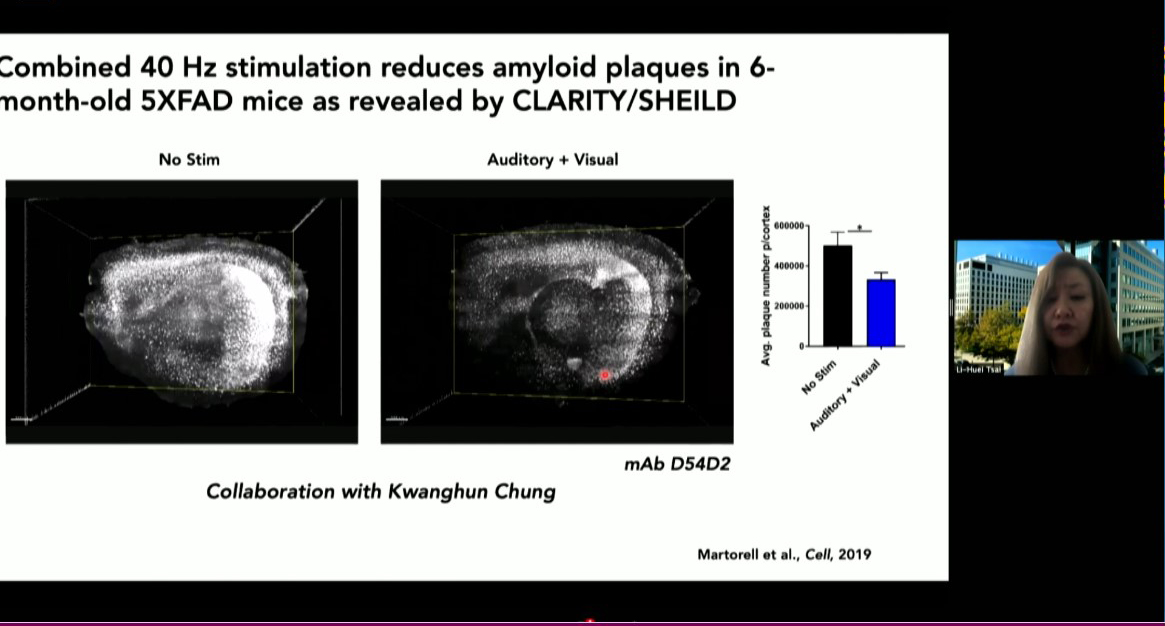

MIT is poised to launch a clinical study of a potential Alzheimer’s therapy among people with Down syndrome, said Alana center co-director Li-Huei Tsai, Picower Professor of Neuroscience at MIT. About five years ago her lab discovered that in Alzheimer’s brain wave power and connectivity at a specific frequency, 40Hz, is notably lessened. They discovered that by exposing lab mice to light flickering and sound buzzing at 40Hz they could restore the rhythm, leading to many benefits including improved learning and memory, reduced neuron death and reductions in the level of toxic tau and amyloid proteins considered hallmarks of Alzheimer’s pathology.

More recently the team has begun clinical studies of the potential therapy, called Gamma ENtrainment Using Sensory Stimuli (GENUS), in humans to test its safety and efficacy in healthy people and in people with Alzheimer’s. Picower Clinical Fellow Diane Chan, the neurologist leading the human studies, said that so far the data indicate that exposure to 40Hz light and sound is safe and may be contributing to improved sleep and a preservation of brain volume in patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease. As soon as conditions related to the Covid-19 pandemic allow, she said, the team will invite people with Down syndrome to enroll in a study to test safety, tolerability and efficacy specifically for them.

Two speakers from Massachusetts General Hospital tackled the important related issue of diagnosing and tracking the progression of Alzheimer’s specifically in people with Down syndrome. Stephanie Santoro, a clinical geneticist with the hospital’s Down syndrome program, described the nationwide LIFE-DSR study, which counts Bartlett among its participants. The study has rigorously developed a suite of assessments to track changes in cognition, behavior, function and health in 270 adults of various ages with Down syndrome over a course of more than 30 months, Santoro said. The results will offer doctors and patients new insights into how aging and Alzheimer’s affect life over time, which may help in screening for Alzheimer’s risk.

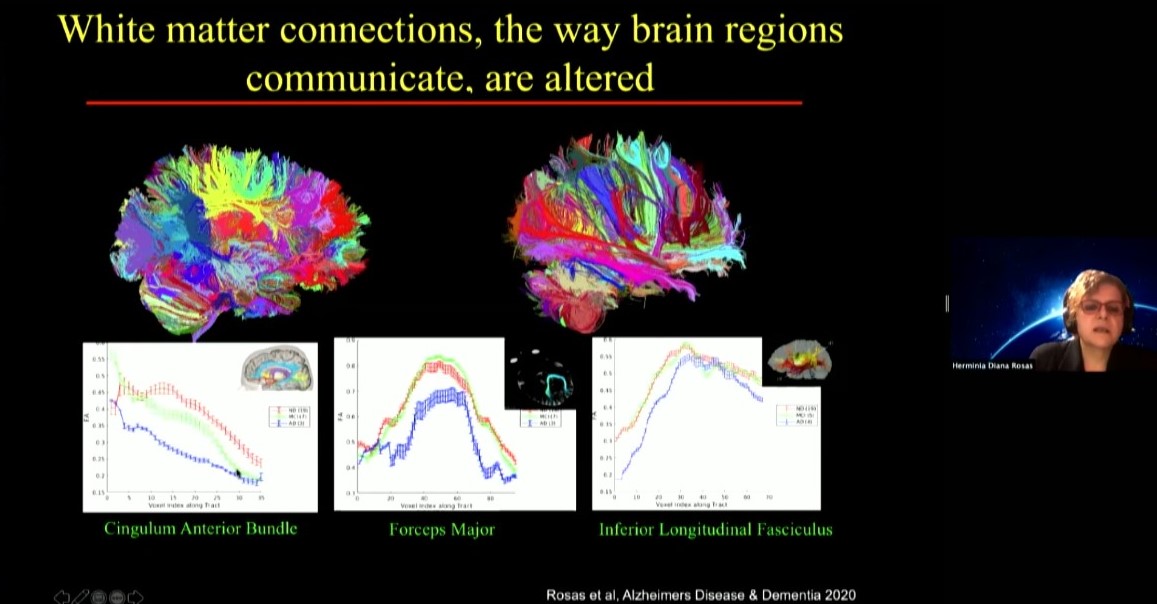

Diana Rosas, an MGH neurologist, is one of the researchers helping to run the LIFE-DSR study. In her talk she focused on another study, the National Institute of Health’s ABC-DS study, in which she is developing biomarkers that may indicate the onset of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s in Down syndrome including data from brain scans, molecule and protein levels measured in blood, and genetic screens. She noted that these markers seeking to track changes over time need to be specific for Down syndrome patients, for instance because they have characteristic differences in brain anatomy compared to people who don’t have the condition.

Another challenge that can hinder learning, memory and cognition in people with Down syndrome is loss of sleep due to breathing trouble. Two symposium speakers discussed new approaches to treating the problem, called sleep apnea, which is very common in people with Down syndrome because of characteristics such as decreased muscle tone, differences in facial anatomy, and larger tongue size. Daniel Combs, a pediatrician at the University of Arizona, described a trial he recently began to test a combination of drugs to treat sleep apnea in children with Down syndrome. The medicines he’s testing have been studied for sleep apnea in non-Down syndrome adults and appear to be helping by increasing airway muscle tone, he said.

Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary otolayrngologist Christopher Hartnick, meanwhile, discussed a surgical approach he is testing for difficult sleep apnea cases. Called hypoglossal nerve stimulation, the procedure involves implanting a breathing sensor on a rib that leads to a processor further up the chest. The processor then stimulates electrodes on muscles of the tongue. When the patient is drawing a breath (sensed at the rib) the processor stimulates the tongue muscles to move the tongue out of the way to improve air flow. This approach has been successful in adults with DS and sleep apnea. So far, Hartnick said, 33 children have been implanted and results look promising.

Fundamental research

At the same time that all of these clinical trials have been progressing, other researchers have been working in the lab to advance more fundamental understanding of the biology going on in cells of people with Down syndrome, often also called trisomy 21 because it is caused by having a third copy of chromosome 21.

Some researchers have forged ahead by working to develop better mouse models of Down syndrome that can more closely reproduce the biology of the condition in the lab. Tarik Haydar of the Center for Neuroscience Research at Children’s National Hospital in Washington DC described his lab’s recent study showing how variations in a predominant mouse model called Ts65dn have led to differing and sometimes contradictory research conclusions that need to be recognized and accounted for.

While important nuances about the Ts65dn model are becoming better understood, Elizabeth Fisher of University College London shared that new mouse models are emerging. In mice the genes that are on human chromosome 21 are spread out over three chromosomes. That has given researchers the challenge of engineering mice to express genes in the same way that people with Down syndrome do. Fisher’s lab has led advances in doing so, and she reported that recently another group managed to directly inserting human chromosome 21 into mice to develop a new model, the TcMAC21 mouse.

Mouse models are crucial because they are whole living organisms that can demonstrate how health and behavior change with an extra chromosome. But another way to model Down syndrome in the lab is by engineering human cell cultures from cells taken from patients. Skin cells, for instance, can be turned into stem cells, which in turn can grow into neurons or heart cells.

MIT biology Professor Laurie Boyer, for instance, has begun studying gene expression in heart muscle cells derived from Down syndrome (DS) persons. The development of the heart is a very intricate and sensitive process and faulty regulation leads to congenital heart defects (CHD). Her goal is to learn how an extra copy of chromosome 21 in DS contributes to the high incidence of CHD that will hopefully fuel potential new therapies for these heart defects.

In other experiments with patient-derived cells—in this case, neurons—Lindy Barrett of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard is finding intriguing overlaps between Down syndrome and a form of autism called Fragile X syndrome. Her lab is finding that the protein missing in Fragile X, called FMRP, normally regulates some genes that are also expressed too much in Down syndrome. The findings, she said, raise the question of whether manipulating levels of FMRP could help Down syndrome patients.

While individual genes, or groups of them, could present new targets for therapies, another goal of the field remains finding a way to repress the activity of the third chromosome 21 as a whole. Speakers Jeanine Lee and Mitzi Kuroda, each of Harvard Medical School, described mechanisms by which various organisms, including humans, naturally suppress or enhance whole-chromosome activity. Females have two X chromosomes but males have an X and a Y. To remedy that imbalance, insects like fruit flies doubly express the X chromosome in males but mammals, like people, suppress or “silence” the activity of one of the X chromosomes in females.

This unusual degree of whole-chromosome up- or down-regulation offers intriguing scientific opportunities. Lee discussed how she hopes to address an autism-like disorder called Rett Syndrome in which girls develop abnormally because a mutant copy of the gene MeCP2 happens to be on one X chromosome they express. Her strategy is to selectively subvert X-chromosome silencing to express the healthy copy of MeCP2 on the inactivated X chromosome. Meanwhile speaker Stefan Pinter of the University of Connecticut discussed how his lab is using the X-chromosome’s silencing machinery to silence the extra chromosome 21 in Down syndrome. Pinter said that by silencing the third copy in developing brain cells in the lab his research group is developing a dynamic model for lab studies in which they can now control chromosome 21 dosage in developing brain cells.

In wrapping up the symposium, Alana Center faculty member Ed Boyden, Y. Eva Tan Professor of Neurotechnology at MIT, said the day provided many individual examples of progress that taken together are even more encouraging.

“Today we have seen many individual examples of research and advocacy from which we can draw inspiration and hope,” he said. “But there is another source of those same feelings as well: the way this community came together today to share and to learn from each other. Even if our interaction was virtual, the growth in our understanding and our interconnection was real.”