Founded at MIT in March 2019, the ADSC brings together neuroscience, biology, engineering and computer science research labs together with the Desphande Center for Technological Innovation to deepen knowledge about Down syndrome and to improve health, autonomy and inclusion of people with the genetic condition characterized by an extra copy of chromosome 21.

The symposium, “Translational Research in Down Syndrome,” brought together experts working across a spectrum of fundamental biology to clinical care. In her opening remarks, ADSC co-director Li-Huei Tsai, Picower Professor of Neuroscience and director of The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, said the event represented a chance for conversation and collaboration among researchers with the common goal of helping people with Down syndrome.

“Informed and inspired by their remarks we can all engage today in learning from each other,” she said. Tsai also thanked Ana Lucia Villela, whose Alana Foundation gift established the center and who had returned to MIT from Brazil to attend the symposium.

‘Aneuploidy’ advances

Throughout the afternoon, speakers shared some of their latest insights into how “aneuploidy,” having an atypical number of chromosomes, alters the biology of cells, the body and the brain.

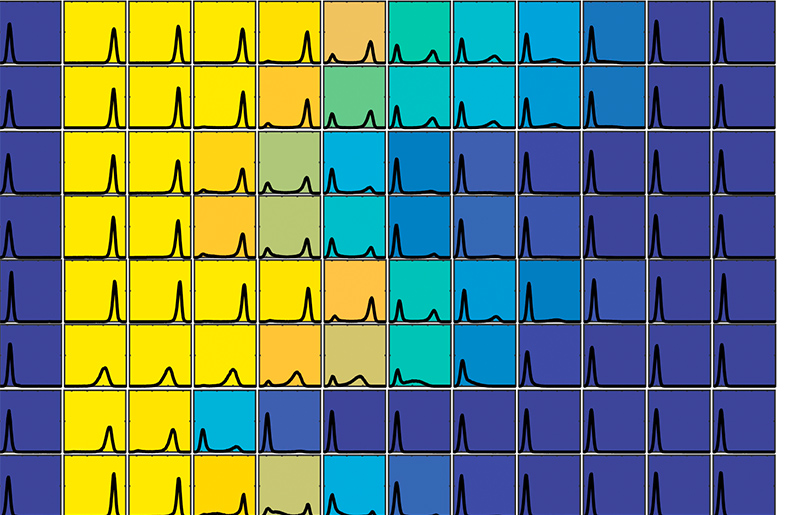

One consequence appears to be that with an extra chromosome, cells make too many copies of the protein subunits that the chromosome encodes. Normally these subunits would become bound with partners encoded elsewhere into larger protein complexes, said ADSC Co-Director Angelika Amon, Kathleen and Curtis Marble Professor of Cancer Research in MIT’s biology department and the Koch Center for Integrative Cancer Research. But there aren’t as many of those partners, so the excess, unbound proteins become prone to clumping together, creating a major clean-up job for the cells that causes ”proteotoxic” stress. In Down syndrome, she said, that stress can hinder growth and proper function. Aneuploidy, she added, might also lead to a greater incidence of DNA damage.

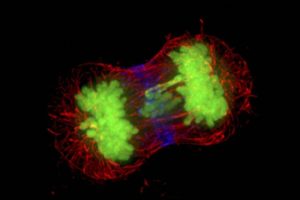

Former Amon lab postdoc Eduardo Torres, who is now at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, said his lab has found that aneuploidy also disrupts the very shape and structure of the nucleus in a variety of cells, making them more sensitive to mechanical stress. The lab looked deeper to find the genetic and molecular pathway responsible and identified one related to the lipid composition of the nucleus. That insight allowed them to discover that administering certain drugs to cells with aneuploidy of chromosome 21 (or 13 or 18) can help shore up the nuclear structure and help cells grow.

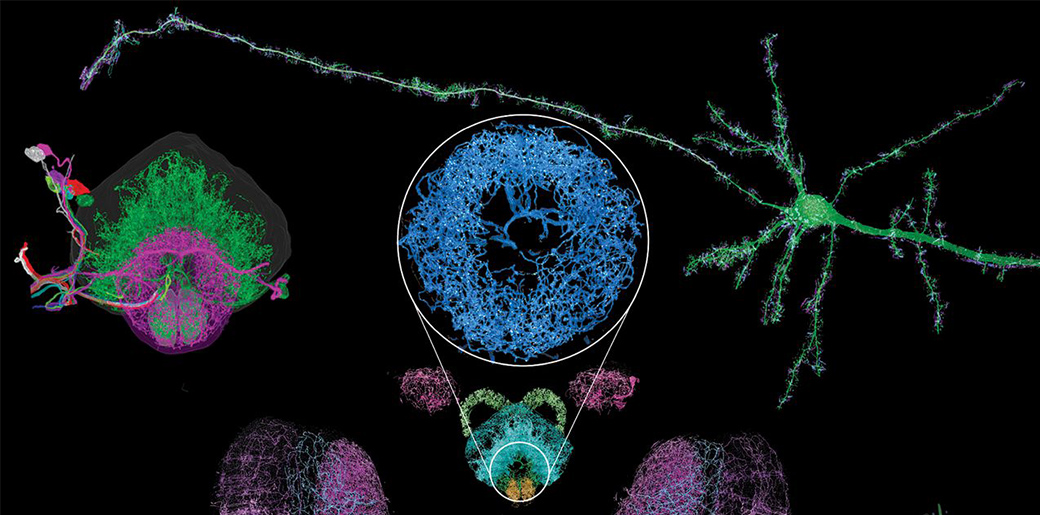

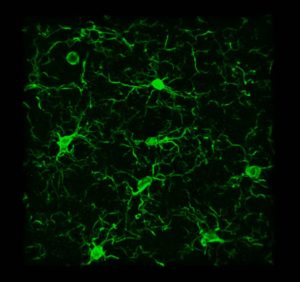

To gain more insight into how aneuploidy affects neurological development many scientists have begun using techniques to grow brain cells from stem cells derived from Down syndrome patients. They can manipulate these cultures in the lab so that the only genetic difference is the extra copy of chromosome 21. Jeanne Lawrence, also of UMass, said use of such advanced models will help her understand whether a technique her lab has developed to silence extra copies of a chromosome will be effective in cells such as those in the brain or blood. Her work shows promise for a potential gene therapy to mitigate the effects of the extra copy of chromosome 21.

Another vital model of Down syndrome is the mouse. In one of the day’s two keynote addresses, Roger Reeves of the McKusick-Nathans Institute for Genetic Medicine at Johns Hopkins University described what researchers have learned from the widely used T65dn mouse model, as well as what they hope to learn from a newly developed model, that uses human chromosome 21 genes to replicate chromosome duplication. He also described their studies of the developmental anomalies in Down syndrome model mouse brains, and have found that a crucial signaling pathway for development is less responsive in these mice. He reported the results of a screen to look for the specific contributors this pathway in DS, as they may be viable targets for drug development, and his lab has also identified some of these same genes to be involved in congenital heart defects.

Clinical care

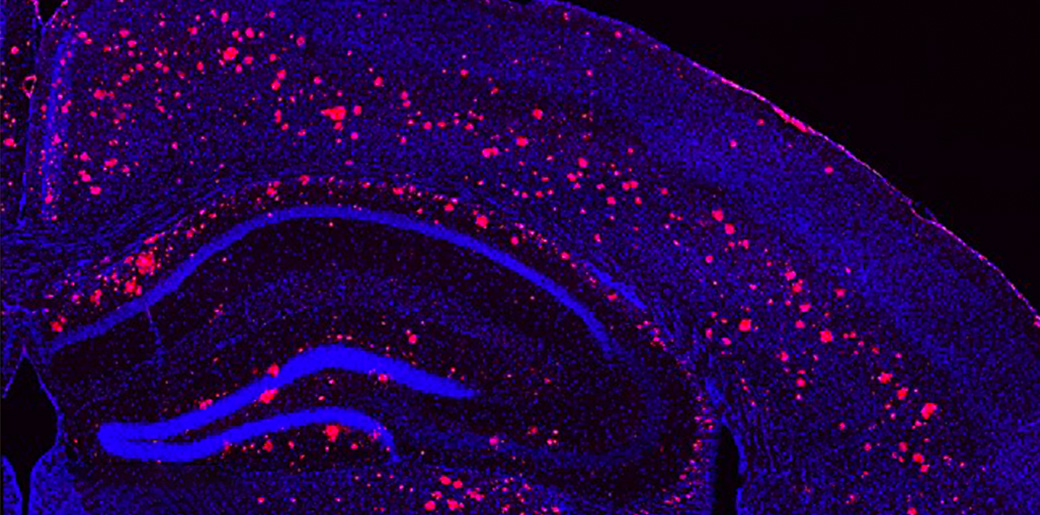

In the symposium’s other keynote, Joaquin Espinosa of the Linda Crnic Institute for Down Syndrome at the University of Colorado, discussed how a fast-emerging raft of insights including discoveries about the immune system in Down syndrome has led to a new clinical trial. Fundamental research at the institute has found that patients with Down syndrome have an increased sensitivity to interferons, proteins emitted by immune cells as they fight infections. The research led scientists to test medicines to calm the immune system. He described their current work on a clinical trial that aims to investigate a drug, Xeljanz, already used for auto-immune disease, to see if the drug not only improves autoimmune skin diseases, but possibly a wider range of symptoms associated with Down syndrome.

Another clinical trial is getting underway at Boston Children’s Hospital, said Nicole Baumer, a researcher there who said there are real opportunities for interventions to improve cognition in Down syndrome patients, but who also cautioned that researchers must always consult patients and their caregivers about what they want from clinical trials and care, rather than assuming what’s best for them. After surveying to learn more about patient and family wishes, her group has designed a study in which they will try to predict the neurodevelopmental outcomes in babies with Down syndrome, and test whether behavioral therapy interventions designed for certain autism populations might also augment intellectual development in children with Down syndrome.

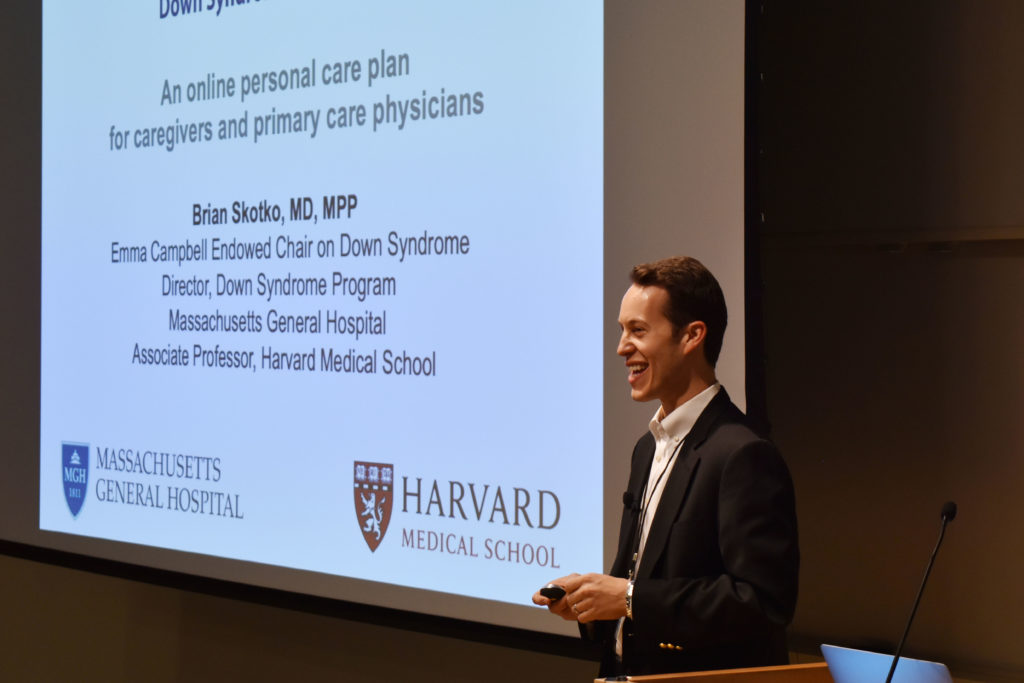

As researchers strive in the lab and clinic to make new discoveries and improve care, Brian Skotko of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School has also been considering how to ensure that state-of-the-art information reaches doctors and family caregivers everywhere it’s needed. Skotko noted that among approximately 212,000 people with Down syndrome in the United States, less than five percent have access to one of the 71 specialty clinics around the country like the one he directs at MGH. Instead, they typically depend on primary care physicians. That’s why he and a diverse team have spent the last two years developing an Internet-based platform, “Down Syndrome Clinic to You (DSC2U)” in which a physician or other caregiver can enter information about a patient and learn richly linked, expert-curated information and recommendations about medical care and wellness customized for the entered patient profile. The clinical team at MGH reviews the underlying database regularly to keep it up to date. With new data showing that the system positively influences care and has been valued by users, it’s ready for a wider launch next year, he said.

Taken together, the symposium talks illustrated many routes to potential progress, from the cell to the clinic.